Wednesday, March 11, 2015

Ink-Slinger Profiles by Alex Jay: Burne Hogarth

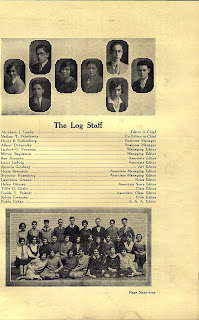

Burne Hogarth was born Spinoza Bernard Ginsburg in Chicago, Illinois on December 25, 1911, according to a profile at AskArt.com: “…Burne Hogarth was my father’s brother, thus I am his niece. He was born Bernard Ginsburg in Chicago, Illinois, on December 25, 1911, though he spent most of his life living in Pleasantville, New York…” His full name was found at Ancestry.com in a Tuley High School yearbook, The Log 1928.

In the 1920 U.S. Federal Census, he was the youngest of two sons born to Max and Pauline, both Russian emigrants. They lived in Chicago at 1252 North Campbell Avenue; an older sister, in the 1910 census, had moved out of the household. His father was a carpenter in a cabinet ship. At BurneHogarth.com Rafael Alvarez posted his biography of Hogarth and said, "…Max kept those sketches and took them and his young son to the Art Institute of Chicago in 1924. Burne was accepted as a student at age 12. By age 15, he was an assistant cartoonist at Associated Editors’ Syndicate. He flourished at the Institute and the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts….Burne graduated high school at the dawn of the Great Depression…."

Comics Scene, #5, September 1982, interviewed Hogarth; here are a few excerpts:

Comics Scene: Give us a capsule history of your career and early background. You graduated from the Chicago Art Institute?

Burne Hogarth: No, I didn’t, as a matter of fact, I went to the Institute but it was only a kind of supplemental activity while I was really in the process of going to high school and at the same time doing art work.

I went to the Art Institute, started Saturday classes, at the age of 12 [1924]. My father thought that I had sufficient material to be able to enroll in classes like that and so he took down a bundle of stuff one day, on a Saturday, and said “Let’s go see what they will think about this.” And they accepted me—so that’s how my training began. Later I went to the Institute taking special courses, but I didn’t enroll in any formal classes. I couldn’t because we were not an affluent family and [the world] was headed into what was later to be known as the Great Depression.

CS: When did you know you had a talent for cartooning?

BH: Very early, when I was a kid, about four. My father would sit and design furniture and cabinets—he was a carpenter and cabinet maker—and I would ask for my own piece of paper and pencil. And when I would say, “What should I draw?” he would push a cartoon under my nose and say “Here, draw this.” So the cartoon became a kind of focus of attention.

CS: What happened after you left the Art Institute?

BH: I enrolled in the Academy of Fine Arts in Chicago. There I studied further drawing and then cartooning as another side of that. That’s when I met a cartoonist who was working for a syndicate and other people who were working for newspapers, and we used to get heavily into what syndication was all about…deadlines and magazines and doing samples and taking them around. I did gags and editorial cartoons, illustrations and that was all part of my portfolio.

I used to take this around and get some jobs in magazines and at the same time worked at odd jobs like driving a truck, selling newspapers and shoes—nothing was too high, too low, or too intermediate to do, because there was obviously an economic necessity.

One of the people I met at the Academy introduced me to one of the syndicates. I worked (for them) in his studio and I was his assistant. I was just an apprentice. I used to come in and sweep up. I learned lettering and I learned also there’s something about the craft of doing work on deadlines. And more than anything else I learned how to use pen, brush, different media and all sorts of things in a very professional way. Maybe two and a half, three years later I sold my first feature to Bonnet Brown. (Many sources called the studio “Barnet Brown” but there was no such company. The Bonnet-Brown Company was mentioned in The Economist, March 13, 1915; Certified List of Domestic and Foreign Corporations for the Year 1920; and The Miami Daily News, October 12, 1926.)

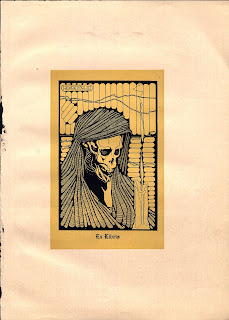

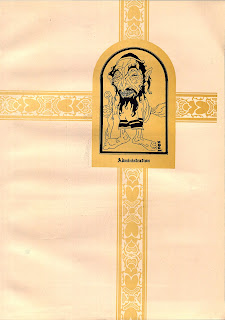

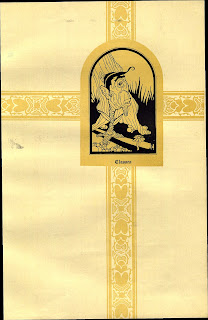

Hogarth was interviewed in the Comics Journal, #166, February 1994, and at age 15, he produced artwork for Associate Editors’ Syndicate’s panels The Sportiest Act I Ever Saw and Famous Churches of the World. He attended Tuley High School although it’s not clear when he graduated. Chicago Public Schools’ CPSAlumni.org website (currently closed) said he was in the class of 1929. The Log 1929, which is available at Memory Lane’s Classmates.com section, does not list or mention Spinoza Bernard Ginsburg. He was the art editor of the 1928 yearbook but it has no picture of him. He signed his name “Hog III” or “Hogarth”; below are pages with his art and the yearbook staff credits.

Hogarth has not been found in the 1930 census. According to a family tree at Ancestry.com, his father passed away in 1930. In the Comics Scene interview, Hogarth said he sold his first series to Bonnet-Brown, a commercial art studio, and it was called

Ivy Hemmanhaw. It was one panel, humorous gags about Americana. I was just 18 [1930]. It lasted about a year and then I went on to teach in the Emergency Educational Program, which came along about the time I was 20-21 [1932–1933], and I went to school, too. I went to Northwestern University, the University of Chicago, and studied psychology, anatomy, sectional anatomy, and then things altered. The Depression got worse and under the urging of friends who had relocated to New York, I made my foray into the field in New York, into the syndicate field, very quickly—and that became the start of a whole new and different part of my life.

Around 1934, Hogarth moved to New York City. According to the 1940 census, he had lived there since 1935. In the Comics Journal interview, he said he visited, on a friend’s advice, King Features and found work. He met Lymon Young who offered him an assistant’s position on Tim Tyler’s Luck because his current assistant, Alex Raymond, was leaving. After two summer months of penciling in Greenwich, Connecticut, he quit and returned to New York. At the McNaught Syndicate he met Charles Driscoll who liked his work and considered him for an Albert Payson Terhune dog project. Hogarth got the job but soon was reassigned to Pieces of Eight, which was written by Driscoll. Hogarth recalled the research involved to produce accurate historical drawings, “…Well, I want to tell you, I started work in February. It was agonizing. I spent 11 hours every day, half the time in the library, and I’d be sitting up nights and working incessantly, and by the end of the week I’d be drained. I’d send this stuff off to the syndicate…I lived the life of a monk in that period….” In the fall, the syndicate decided to end the strip. Hogarth said, “…‘Thank God this thing is over! I’m through with it’. The pirate strip was the heaviest chore I ever carried. And I was glad it as over.” Two weeks of his Pieces of Eight can be viewed here and here.

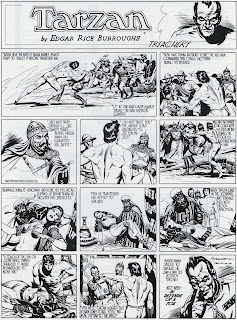

In the winter of 1937 he visited United Features and learned that Hal Foster was leaving the Tarzan strip. Hogarth accepted the invitation to submit samples. Later he learned he got the assignment because the United Features general manger could not tell the difference between his and Foster’s work. His first Sunday page appeared May 9, 1937 and the last on November 25, 1945. A dispute with the syndicate led to Hogarth’s departure. After Tarzan, he produced the strip, Drago, for the Robert Hall Syndicate.

#533,10/12/1941;

Russ Cochran’s Graphic Gallery #6

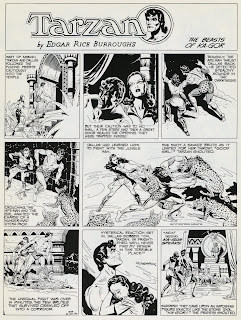

#633, 4/25/1943;

Russ Cochran’s Comic Art Auction #44

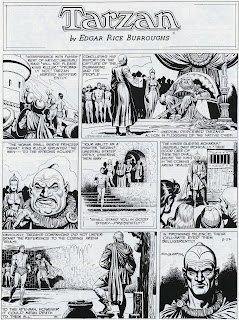

#665, 12/5/1945;

Russ Cochran’s Comic Art Auction #42

#666, 12/12/1945;

Russ Cochran’s Comic Art Auction #42

#859, 8/24/1947;

Russ Cochran’s Comic Art Auction #28

In 1940, Hogarth was married to Rhoda and, since 1935, lived at 26 West 74th Street in New York City. The Manhattan Telephone Directory 1942 had his home address at 66 West 88th Street. His business address was 2091 Broadway in the 1945 directory. In the Comics Journal #167, April 1994, when asked how the School of Visual Arts started, he said around 1945 war veterans began contacting him for cartooning advice. He would invite them to his apartment, on Saturdays, to give advice and do demonstrations. To accommodate the growing number of veterans, he looked around his neighborhood and found space at a private secondary school, which was a high school. There he met Silas Rhodes, an English teacher, who suggested that he open a school. Hogarth asked what was involved and Rhodes explained the procedures. Hogarth recalled that he rented a loft on 72nd Street and Broadway and called it the Academy of Newspaper Art. A search of that name produced nothing, however, a series of small advertisements for the Cartoonists & Illustrators Center appeared in October 1945 issues of the New York Post.

New York Post 10/10/1945

LEARN CARTOONING

With One of the Leading

Cartoonists in the Field

BURNE HOGARTH

OF “TARZAN” FAME

Classes Start October 16th, Eves. & Saturdays

Write for Information NOW!

CARTOONISTS & ILLUSTRATORS CENTER

2091 Broadway, New York, 23, N.Y.

New York Post 10/19/1945

PLAN YOUR CAREER NOW

Learn Cartooning with

BURNE HOGARTH

The demand for original cartoonists grows daily.

Comprehensive course in cartooning and illus-

trating. Special courses for advanced students.

CARTOONISTS & ILLUSTRATORS CENTER

BURNE HOGARTH (of Tarzan Fame, Dir.)

2091 Broadway at 72nd St. TRafalgar 4-6616

New York Post 10/26/1945

LEARN CARTOONING With BURNE

HOGARTH of “TARZAN” fame. New complete

intensive course for beginners and ad-

vanced students.

Cartoonist & Illustrators Center

2091 B’way (72nd St. N.Y.C.) TR 4-6616

When the Center outgrew the loft space, Hogarth found space at a secondary school that opened in the evenings. There he could easily add classrooms as needed. In 1946, nearly identical advertisements ran in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 10, and Arts Magazine, February 15.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle 2/10/1946

LEARN CARTOONING

With A Leading Cartoonist

BURNE HOGARTH

of “TARZAN” fame

Now is the time to get

into the cartooning field!

Learn the technique of

newspaper and magazine

panel gags — sport car-

toons — comic strips —

caricature advertising

comic illustrations.

Classes: SATURDAYS ONLY

(Mornings & Afternoons)

CARTOONISTS & ILLUSTRATORS CENTER

ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON SCHOOL

246 West 80 N.Y.C. SC 4-3232

The Center was certified by the State Education Department, in 1947, and renamed the Cartoonists and Illustrators School. The New York Times, January 19, 1956, said the school opened August 20, 1947. The school was mentioned in the Post, November 10, 1947.

Classes are still forming at the Cartoonists and Illustrators School, 112 W. 89th St., it was announced by Silas H. Rhodes, director. Nationally prominent cartoonists and illustrators, headed by Burne Hogarth, illustrator of “Tarzan,” comprise the faculty and lecturing staff.

During Hogarth’s absence, Ruben Moreira had been drawing the Tarzan Sunday page from December 2, 1945 to August 3, 1947. According to ERBzine, Hogarth returned to Tarzan for the next three years, from August 10, 1947 to August 20, 1950. And for about four months, he also worked on the Tarzan daily from September 1, 1947 to January 3, 1948. Miracle Jones was short-lived strip he produced in 1947, a very busy year.

At the Silver Lantern site, Sy Barry recalled visiting Hogarth’s apartment:

Hogarth and Rhodes were accused of being Communists, as reported January 19, 1956, in the Long Island Star Journal (below), the Milwaukee Sentinel (Wisconsin), and other papers. Both men invoked the Fifth Amendment. Later that year, the Cartoonists and Illustrators School was renamed the School of Visual Arts.

Suburbia Today, June 12, 1983, profiled Hogarth’s second wife, Connie, and said:

The University of Chicago Magazine, October 2006, published the following sequence of events:

The Dispatch (Lexington, North Carolina), November 9, 1963, published Hogarth’s article, “Our American Art Heritage.” In 1970 he retired from the School of Visual Arts due to differences with Rhodes. He continued to teach at Parsons School of Design. In this decade he returned to Tarzan by producing two books, Tarzan of the Apes (1972) and Jungle Tales of Tarzan (1976). His first book, Dynamic Anatomy, was published in 1958. Following it were Drawing the Human Head (1965), Dynamic Figure Drawing (1970), Drawing Dynamic Hands (1977), Dynamic Light and Shade (1981), Dynamic Wrinkles and Drapery (1988), and The Arcane Eye of Hogarth (1992).

In the early 1980s he settled in Los Angeles, California, where he continued teaching at the Otis School and Art Center College of Design. After attending the Angoulême International Comics Festival in France, Hogarth suffered a heart-attack in Paris and passed away January 28, 1996.

…When I got to meet Bernie Hogarth, I went up to his studio, which was in his apartment. My brother [Dan Barry] had an apartment like that later on.

You would go into the main area of the apartment and it was one step down into the living room area, but there was also a staircase at the end of the living room that went upstairs to the bedrooms, in an apartment house, believe it or not. I don’t know how they designed this thing, but it was really remarkable. So you’d go up the staircase and there’d be a landing there and that landing would take you into the bedrooms. Then in one of the upstairs bedrooms was his studio. It was this beautiful, brightly lit studio and it was on Central Park West.

It was a beautiful apartment and of course he was very wealthy. He’d written anatomy books and he taught and of course they paid him very handsomely on the Tarzan daily. Trust me, he was very well paid, especially for those Sunday strips. He was a brilliant guy….

Hogarth and Rhodes were accused of being Communists, as reported January 19, 1956, in the Long Island Star Journal (below), the Milwaukee Sentinel (Wisconsin), and other papers. Both men invoked the Fifth Amendment. Later that year, the Cartoonists and Illustrators School was renamed the School of Visual Arts.

Suburbia Today, June 12, 1983, profiled Hogarth’s second wife, Connie, and said:

…By the mid-1950s she had met artist Burne Hogarth, famous as the man who drew the Tarzan comic strip. They soon married and had two children….

...In 1962, the Hogarths moved from their Queens apartment in search of more space for the boys and a studio for Burne. In Mount Pleasant [New York], they found a fortress of a house, resembling something out of Charles Addams….

...Her personal life has also become a testing ground. She and Burne were divorced last year....

The University of Chicago Magazine, October 2006, published the following sequence of events:

...In 1953 she married cartoonist Burne Hogarth, who drew the Tarzan comic strip (1937–50) and founded the art school that became New York’s School for the Visual Arts [sic]. Soon after son Richard was born in 1956 and son Ross in 1959, the Hogarths moved to suburban Westchester County, which had a reputation for good public schools. (She and Burne divorced in 1981, and nine years ago she married Art Kamell, a longtime activist and former labor lawyer.)

The Dispatch (Lexington, North Carolina), November 9, 1963, published Hogarth’s article, “Our American Art Heritage.” In 1970 he retired from the School of Visual Arts due to differences with Rhodes. He continued to teach at Parsons School of Design. In this decade he returned to Tarzan by producing two books, Tarzan of the Apes (1972) and Jungle Tales of Tarzan (1976). His first book, Dynamic Anatomy, was published in 1958. Following it were Drawing the Human Head (1965), Dynamic Figure Drawing (1970), Drawing Dynamic Hands (1977), Dynamic Light and Shade (1981), Dynamic Wrinkles and Drapery (1988), and The Arcane Eye of Hogarth (1992).

In the early 1980s he settled in Los Angeles, California, where he continued teaching at the Otis School and Art Center College of Design. After attending the Angoulême International Comics Festival in France, Hogarth suffered a heart-attack in Paris and passed away January 28, 1996.

Labels: Ink-Slinger Profiles

Comments:

I took Burne's evening drawing course at Otis/Parsons in 1985 and socialized with him a bit. Burne still loved coffee-shop intellectualizing, and had some peculiar ideas: Jackson Pollock's paintings were depicting atomic structure, and the word "Christmas" could be traced etymologically to a time before Christ.

Nevertheless, he was delightful and his drawing demos were a occasions of jaw-dropping wonder. When he sat down to correct one of my drawings, he couldn't stop himself and worked for fifteen minutes. So I have what I consider a Hogarth original.

I met my wife Elizabeth in that class, too. She was another student.

Years later Archie Goodwin told me Burne exhorted a gathering of comics professionals who were discussing forming a guild or union that they should en masse join the Communist party. The suggestion landed with a wet thud on the floor.

Post a Comment

Nevertheless, he was delightful and his drawing demos were a occasions of jaw-dropping wonder. When he sat down to correct one of my drawings, he couldn't stop himself and worked for fifteen minutes. So I have what I consider a Hogarth original.

I met my wife Elizabeth in that class, too. She was another student.

Years later Archie Goodwin told me Burne exhorted a gathering of comics professionals who were discussing forming a guild or union that they should en masse join the Communist party. The suggestion landed with a wet thud on the floor.